Western Sahara at a Crossroads: Does UN Resolution 2797 Protect Sahrawi Rights or Entrench Occupation?

- Mila Roth

- Nov 25, 2025

- 6 min read

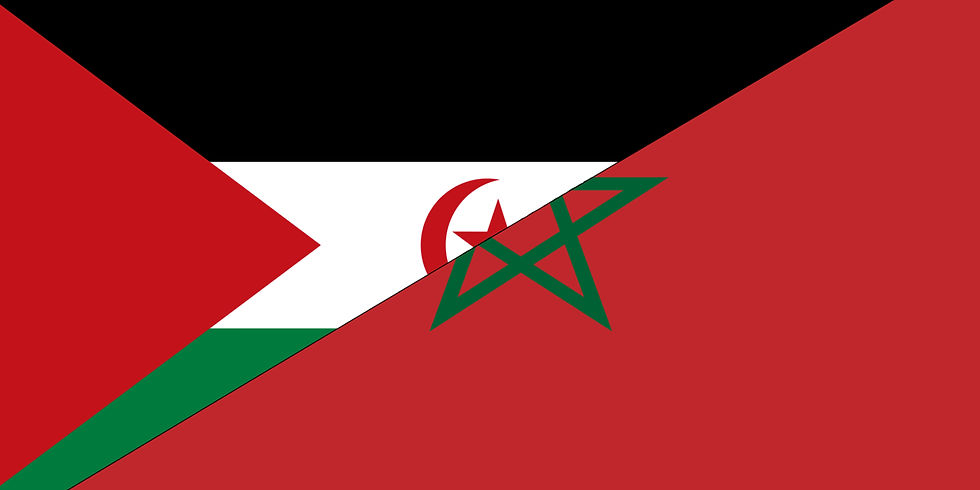

Does UN Resolution 2797 offer a better framework for resolving the occupation of Western Sahara, or does it risk entrenching the conflict and worsening conditions for the Sahrawi people?

Introduction

Western Sahara is widely described as “one of the world’s last vestiges of colonialism” and

remains the only major territory on the UN’s list of non-self-governing regions. Spain’s 1975

withdrawal was followed by the occupation of Morocco, triggering a war with the Polisario

Front and leaving the Sahrawi people divided between Moroccan-occupied areas, a small

“free zone,” and long-term refugee camps in Algeria housing around 173,000 people where

On 31 October 2025, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2797, renewing MINURSO

and endorsing Morocco’s 2007 Autonomy Plan as the basis for negotiations. Supporters

frame this as a pragmatic step toward stability; critics argue it sidelines Sahrawi self-determination and legitimises an occupation marked by decades of repression. This article assesses whether the resolution advances Sahrawi sovereignty or deepens their vulnerability, focusing on the core issue: without human-rights monitoring, can any political settlement protect Sahrawi rights?

Understanding Resolution 2797

MINURSO’s human-rights gap

MINURSO is the only modern UN peacekeeping mission without a human-rights mandate. As Naili argues, this omission is structurally consequential: abuses including arbitrary detention, torture, enforced disappearances, and suppression of Sahrawi language and activism are “systematically excluded from UN reporting”.

This absence does not simply miss violations — it actively shapes the international

community’s understanding of the conflict, allowing states to negotiate political arrangements without confronting the lived realities of repression.

The lack of oversight is significant given that rights groups have documented hundreds of political arrests since 2010 and near-constant restrictions on journalists and NGO access. Resolution 2797 again renewed MINURSO without adding rights monitoring, despite OHCHR’s longstanding recommendation that peacekeeping mandates integrate human-rights protection. By continuing to omit human rights monitoring, the UN effectively narrows what counts as evidence, and encourages a political process built on incomplete information that is insufficient in safeguarding Sahrawi rights.

Independence under Moroccan Sovereignty

Scholars note that Moroccan control has historically been driven by strategic resource extraction and regime consolidation rather than decolonisation principles. Morocco has transferred large numbers of settlers into the territory — contrary to the Geneva Conventions — and provided tax incentives, housing, and employment to encourage demographic change.

Meanwhile, Sahrawis often face discrimination in employment, policing, and public services. Economic marginalisation is clear: Morocco profits from phosphates, fisheries, and renewable energy, with the Bou Craa mine alone producing around 2–3 million tonnes of phosphates annually, while Sahrawis lack stable access to clean water, electricity, and land. These patterns raise serious doubts about autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty. If the autonomy plan were adopted under current conditions, Morocco would be able to enter the new arrangement as the dominant actor – controlling land, resource flows and security forces. This imbalance severely undermines the possibility of ‘shared governance’ and makes coercive assimilation more likely than genuine power-sharing.

Without oversight, autonomy risks institutionalising inequality rather than resolving it. By locking disparities into a formal political framework, autonomy could transform temporary occupation into long-term structural domination.

What Resolution 2797 entails:

a. Extends MINURSO and requests a six-month review;

b. Describes Morocco’s Autonomy Plan as “a serious and credible basis” for a solution;

c. Reaffirms self-determination without explicitly guaranteeing independence.

Morocco, France, the US, Spain, and now the UK publicly present the Autonomy Plan as the “only viable” framework. Polisario and Algeria, by contrast, denounce the resolution as a violation of UN decolonisation doctrine and refuse to participate in talks that “legitimise occupation”.

As Istrefi argues, the Council is now operating “between self-determination and implicit recognition of Moroccan sovereignty”. In practice, Resolution 2797 tilts hard toward the latter, while doing nothing to correct MINURSO’s human-rights blind spot. Crucially, the resolution does nothing to address the 50-year absence of human-rights protection — making it inadequately equipped to address Sahrawi insecurity.

Proponents argue that autonomy is the only politically viable solution after decades of stalemate, noting that an independence referendum remains blocked and that Moroccan administration ensures regional stability in an increasingly volatile Sahel. Some suggest gradual rights improvements under autonomy could provide Sahrawis more immediate material gains. However, as Zunes and Mundy point out, forced political settlements without rights protections rarely produce lasting peace. Naili similarly argues that MINURSO’s lack of a rights mandate guarantees ongoing repression, regardless of political formula. Thus, even realist arguments do not override the need for enforceable human-rights safeguards and meaningful Sahrawi participation.

Policy Recommendations

Add a Human-Rights Mandate to MINURSO

Integrating a human-rights mandate into MINURSO would directly address the structural invisibility of violations in Western Sahara. Currently, violations including arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances, suppression of protest, and restrictions on journalists, do not enter formal UN reporting channels due to the lack of a mandate. Adding monitoring and public reporting would deter abuses, create accountability mechanisms, and ensure that Sahrawi testimonies reach diplomatic forums. Without this foundation, no political process can genuinely protect Sahrawi civilians.

Guarantee a genuine self-determination mechanism

A meaningful political settlement requires an authentic self-determination process. This means presenting Sahrawis with all legally recognised options and allowing them to select freely. Including displaced refugees, occupied-zone residents, and diaspora communities ensures the vote reflects the entire Sahrawi nation rather than Morocco-controlled demographics. Participation from the African Union offers an essential decolonisation safeguard, balancing geopolitical pressure from powerful UNSC members and grounding the process in continental norms of mutual cooperation. A credible mechanism would restore trust, reduce the likelihood of renewed armed conflict, and align the resolution with international law.

Embed resource justice and socio-economic rights

Sahrawi marginalisation is not only political but economic. Morocco’s control over phosphates, fisheries, and renewable energy projects generates significant revenue while Sahrawis face high unemployment, and limited access and discrimination to essential public services. Embedding resource justice – such as benefit sharing frameworks, job guarantees, and land-use rights – ensures the population directly benefits from their own natural wealth. Protecting Hassānīya language and cultural rights strengthens collective identity and counters decades of enforced assimilation. These measures would materially improve daily life, reduce structural inequalities, and make any political settlement sustainable rather than symbolic.

Conclusion

Resolution 2797 signals renewed UN engagement but does little to address the fundamental obstacle to peace: the systematic denial of Sahrawi rights under occupation. With 173,000 refugees still in camps and Moroccan-controlled zones marked by ongoing political arrests and economic exclusion, endorsing the Autonomy Plan without a human-rights mandate risks entrenching a deeply unequal status quo. A durable settlement requires rights-based guarantees that centre Sahrawi dignity, protection, and political agency. Without this, the resolution will stabilise diplomacy far more than it delivers justice.

Bibliography

ACAPS. Algeria: Sahrawi Refugees in Tindouf. Briefing Note, 19 Jan. 2022. ACAPS

Allan, Joanna. “Natural Resources and Intifada: Oil, Phosphates and Resistance in Western Sahara.” 2016. eprints.whiterose.ac.uk

Amnesty International. Morocco/Western Sahara: UN Must Monitor Human Rights. 2019. Amnesty International

Camps-Febrer, Blanca. “Caught in the Fishers’ Net? The Colonial Plunder of Western Sahara’s Seas.” Review of African Political Economy, 2025. scienceopen.com

Istrefi, Kushtrim. “The Security Council and the Western Sahara: Between Self-Determination and Implicit Recognition of Moroccan Sovereignty.” EJIL: Talk!, 4 Nov. 2025. EJIL: Talk!

Khakee, Anna. “The MINURSO Mandate, Human Rights and the Autonomy Proposal.” The Journal of North African Studies, 2014. tandfonline.com

Naili, Meriem. Peacekeeping and International Human Rights Law: Interrogating United Nations Mechanisms through a Study of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. Order No. 30397412 University of Exeter (United Kingdom), 2022 EnglandProQuest. 20 Nov. 2025 .

Reuters. “UN Calls for Western Sahara Talks Based on Morocco’s Autonomy Plan.” 31 Oct. 2025. Reuters

Reuters. “France Backs Moroccan Sovereignty over Western Sahara.” 30 July 2024.

Reuters San Martín, Pablo. Western Sahara: The Refugee Nation. 2010. shs.cairn.info

“The POLISARIO Front Reiterates Its Rejection of Any Negotiation Legitimizing the Moroccan Occupation.” No te Olvides del Sáhara Occidental, 27 Oct. 2025.

The Guardian. “UK Swings behind Morocco’s Autonomy Proposal for Western Sahara.” 1 June 2025. theguardian.com

United Nations Security Council. S/PV.10030: 10030th Meeting, 31 October 2025, The Situation Concerning Western Sahara. 31 Oct. 2025,

United Nations Security Council. “With 11 Members Voting in Favour, 3 Abstaining, Security Council Adopts Resolution 2797 (2025), Renewing Mandate of UN Mission in Western Sahara.” United Nations Press Release SC/16208, 31 Oct. 2025.

Zunes, Stephen, and Jacob Mundy. Western Sahara: War, Nationalism, and Conflict Irresolution. Syracuse University Press, 2010. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1j2n9vz